Despite the excitement that 3-D printing has generated, its capabilities remain rather limited. It can be used to make complex shapes, but most commonly only out of plastics. Even manufacturers using an advanced version of the technology known as additive manufacturing typically have expanded the material palette only to a few types of metal alloys. But what if 3-D printers could use a wide assortment of different materials, from living cells to semiconductors, mixing and matching the “inks” with precision?

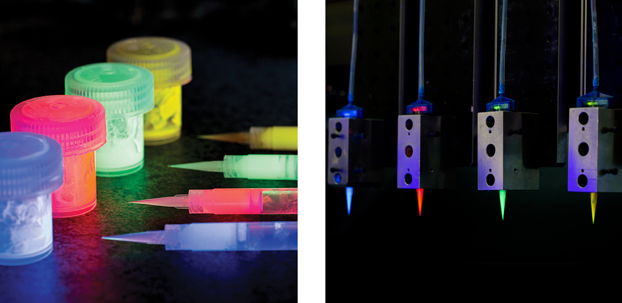

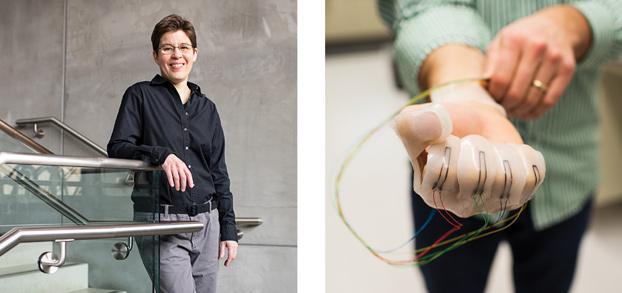

Jennifer Lewis, a materials scientist at Harvard University, is developing the chemistry and machines to make that possible. She prints intricately shaped objects from “the ground up,” precisely adding materials that are useful for their mechanical properties, electrical conductivity, or optical traits. This means 3-D printing technology could make objects that sense and respond to their environment. “Integrating form and function,” she says, “is the next big thing that needs to happen in 3-D printing.”

A group at Princeton University has printed a bionic ear, combining biological tissue and electronics (see “Cyborg Parts”), while a team of researchers at the University of Cambridge has printed retinal cells to form complex eye tissue. But even among these impressive efforts to extend the possibilities of 3-D printing, Lewis’s lab stands out for the range of materials and types of objects it can print.

Last year, Lewis and her students showed they could print the microscopic electrodes and other components needed for tiny lithium-ion batteries (see “Printing Batteries”). Other projects include printed sensors fabricated on plastic patches that athletes could one day wear to detect concussions and measure violent impacts. Most recently, her group printed biological tissue interwoven with a complex network of blood vessels. To do this, the researchers had to make inks out of various types of cells and the materials that form the matrix supporting them. The work addresses one of the lingering challenges in creating artificial organs for drug testing or, someday, for use as replacement parts: how to create a vascular system to keep the cells alive.

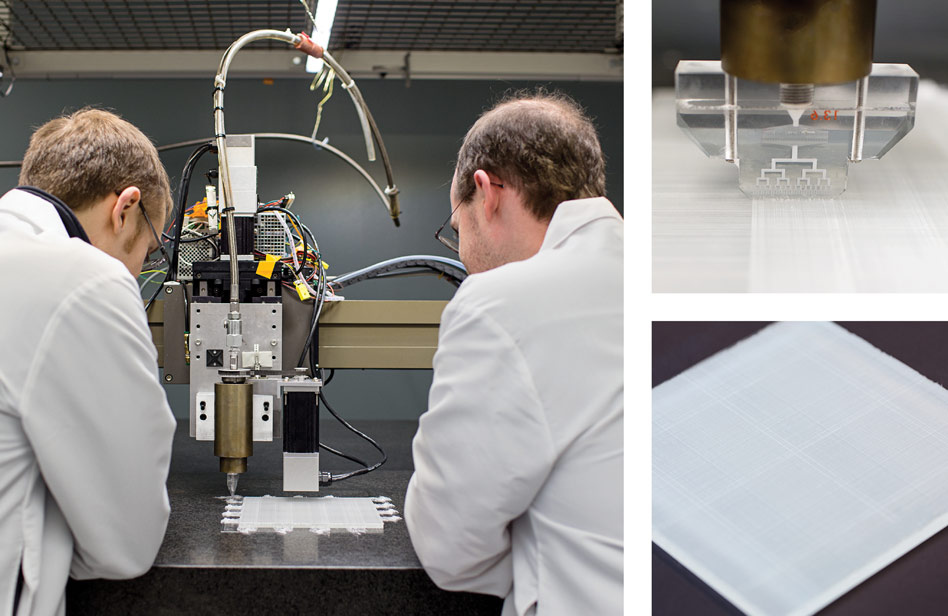

In a basement lab a few hundred yards from Lewis’s office, her group has jury-rigged a 3-D printer, equipped with a microscope, that can precisely print structures with features as small as one micrometer (a human red blood cell is around 10 micrometers in diameter). Another, larger 3-D printer, using printing nozzles with multiple outlets to print multiple inks simultaneously, can fabricate a meter-sized sample with a desired microstructure in minutes.

The secret to Lewis’s creations lies in inks with properties that allow them to be printed during the same fabrication process. Each ink is a different material, but they all can be printed at room temperature. The various types of materials present different challenges; cells, for example, are delicate and easily destroyed as they are forced through the printing nozzle. In all cases, though, the inks must be formulated to flow out of the nozzle under pressure but retain their form once in place—think of toothpaste, Lewis says.

Before coming to Harvard from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign last year, Lewis had spent more than a decade developing 3-D printing techniques using ceramics, metal nanoparticles, polymers, and other nonbiological materials. When she set up her new lab at Harvard and began working with biological cells and tissues for the first time, she hoped to treat them the same way as materials composed of synthetic particles. That idea might have been a bit naïve, she now acknowledges. Printing blood vessels was an encouraging step toward artificial tissues capable of the complex biological functions found in organs. But working with the cells turns out to be “really complex,” she says. “And there’s a lot more that we need to do before we can print a fully functional liver or kidney. But we’ve taken the first step.”

—David Rotman